What's In Your Future?

We here at the Dougloid Papers have a benign approach to the somewhat arcane subject of futures trading, except as it impinges on our daily affairs.

For the unitiated, futures trading is a vehicle where contracts for the future delivery of fungible goods are bought and sold on an exchange. such as the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), Dalien Commodity Exchange (DCE), New York Mercantile and so on. The contracts are in standard denominations: so many tons of number 2 yellow corn, so many tons of soy oil, so many barrels of crude oil, so many gallons of number 2 fuel oil, to be delivered at a place certain on a date certain some months in the future. Contracts mature at set times of the year.

There are two types of people who trade in futures-hedgers and speculators.

A hedger is an end user or a producer of the product, and the hedger will take a position in that product so as to fix future prices for his mill, processing plant, or brewery. Knowing what you're going to pay a few months down the road for jet fuel or corn is a valuable and useful tool in the world of business. A hedger-producer may also sell contracts for his future production of corn or fuel oil and thereby lock in a price he will receive, often before the corn is planted or the oil is refined. Knowing what you'll be paid for your product six months or a year down the road is also valuable information.

Speculators, on the other hand, trade in contracts, not products although hedgers often speculate as well as hedge. A speculator will buy contracts and bet that the market price will go up. If that happens, the speculator sells the contracts and pockets the difference. That's called selling long.

Short selling is the opposite. The short seller is betting that the market will go down. So what the short seller does is borrows contracts, betting that he can replace them in the future at a lower price and pocket the difference.

So. How does the speculator or trader know what direction the market's going to go? Because they're in the knowledge business. The astute speculator is like the professional bettors you see out at the track at six a.m. watching the horses train, or one who marshals the statistics and sees an edge somewhere that can be exploited.

Either way, the landscape is littered with the bleached bones of people who thought they had an inside track on where the market was going. I was acquainted with a mechanic at Garrett back in the day who'd received a settlement of about $50,000 clear from an auto accident and sunk the entire roll into a precious metals trading company that would 'buy' gold on your account and keep your book on paper-essentially you were buying not the gold itself, but a position.

Inside of a month, Mike was worth $100,000 on paper and as he came to the shop and collected his toolbox he looked over at me and a couple other fellows and said with scarcely veiled contempt "How does it feel having to work for a living?".

Well. In a series of disastrous trades in the next few months month the trading company lost Mike's roll and he went upside down big time. That was in 1980, a year that gold hit about $650 per ounce and then lost $150 in three months time. There were some pretty tough looking fellows coming around asking for Mike, and last I'd heard he'd headed for the backwoods of Vermont.

I myself was involved in some 'hedge to arrive' litigation back in the late nineties and a lot of people got their clocks cleaned permanently and are now waitresses and gas station pump jockeys. The mighty, as they say, fell.

It is a most dangerous way to make money.

Now. To the matter at hand.

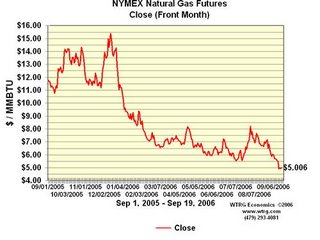

Everyone remembers what happened to their heating bills last winter when the price of natural gas spiked and dragged the price of home heating oil along with it. It was pretty tough here in the midwest to heat the house at those prices. Amaranth Advisors LLC is a hedge fund-trading house that trades natural gas futures, and they bet heavily that the winter price of natural gas was going nowhere but up. They staked out a position, only to have the prices for natural gas tank on news that the winter may not be as cold as expected. As of this writing, Amaranth had lost half its $9 billion roll, and was fixing to lose most of the rest.

As for me, it'll be a welcome break knowing that my heating bill may well decline by 30 or 40 per cent this winter. I shall not lose too much sleep over this year's Enron.

Credit for the chart belongs to WTRG Economics and the NYMEX. Thanks, fellows.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home